Our team was asked to answer some queries about how it’s possible to receive mail that has been forged as being from your email address. This article slightly overlaps with a previous article in 2011 that covered similar ground. Please note that the target audience for this article is end users, not technical support staff and so some of the technical descriptions (and especially the diagrams) are simplified in order to explain the overall theory or process.

Someone is sending mail as being from my address, how is that possible?

It’s best to think of emails as postcards. Anyone can write on the postcard a false sender – anyone could send you a postcard ‘from’ you and the postman would still deliver it.

How can I stop someone outside the university receiving an email pretending to be from me?

One of the most reliable ways to establish that a mail if from you is to install, setup and use PGP/GnuPG mail signing on your mail client and have the receiver of your mail always check that the signature is valid. This can be complicated at first and it’s best to involve your local IT support.

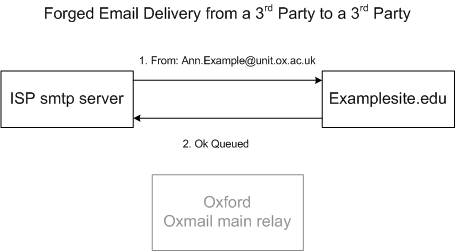

This is does not perfectly address the question however. People on the internet will still be able to send email as your sender address and the recipient outside the university may or may not check the signature. To explain why it is possible for the university not to be able to affect this, here’s a diagram showing a mail being delivered from an Internet Service Provider (ISP, like BT, or Virgin Media) to a destination site with the sender address forged:

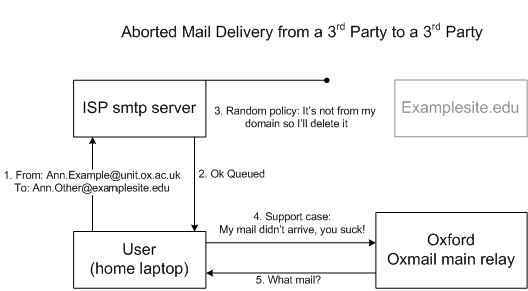

I’ve simplified the communications involved but you’ll notice that there’s no involvement with the university systems in the above diagram. The university will have no logs or any other interaction in the above example. This is one reason why we ask that all legitimate mail for the domains of ox.ac.uk are sent through the university systems, consider this scenario:

When someone sends mail via a 3rd party mail submission server we don’t have any involvement. Imagine you gave a physical letter to a coworker to hand deliver, it didn’t arrive and then you tried to complain to the postman – it’s a similar scenario.

I’ve heard that SPF is the answer to this.

In an ideal world (or for a small company), SPF would be of immediate use but the University of Oxford mail environment does not currently match what SPF wants to describe. We can use it for increasing the spam score of inbound mail but we can’t reject on it nor currently publish a restrictive SPF record designating exactly which mail servers can send mail for ox.ac.uk domains. I’ll explain further.

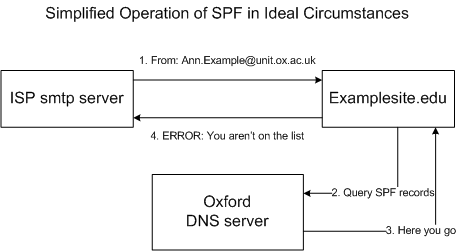

With SPF we essentially state in a public DNS record “the following servers can send mail for the ox.ac.uk domain”, the idea is that the receiving server checks if the mail server that has sent them the mail matches the list of authorised sending mail servers. The following diagram shows the basic process in action:

So in this example the ISP SMTP server contacts a 3rd party site and attempts to deliver a message that’s from an address at ox.ac.uk. The site being delivered to looks up our SPF records and sees that the SMTP server that’s trying to deliver to it is not listed as a valid server for our domain and so rejects the mail. Sounds perfect? Sadly there are a number of problems with this

- Firstly, even if there were no other problems, there is no way we can enforce that a 3rd party receiving site is checking SPF records for inbound mail for mail it receives from other 3rd party servers.

- Secondly we hit a problem with the list of ‘authorised servers’ specifically that even if the 20 or so separate units with SMTP exemptions to the internet are included in the list, we then have to include any NHS mail servers, any gmail.com mail servers and a selection of other sources where users are currently legitimately sending as their university addresses but from a 3rd party. Each time we open up one of these online services, the SPF rules become less useful, since now anyone on gmail or NHS servers could send as any ox.ac.uk address and pass the SPF test.

- Thirdly, we need the receiving sites not to break (refuse messages) if messages are forwarded and we have strict SPF records in place

A solution to the later problem would be a university wide decree that mail sent from ox.ac.uk must go via the university mail servers. That’s not likely to be a popular idea but I list it for completeness, I’ll discuss this further in the conclusion.

You could still check SPF inbound to the university in general though?

Yes, we’ve done some work in this area. It’s not a boolean solution to anything however as some spammers have perfect SPF records and some legitimate sites have broken SPF records. We could increment the spam score based on the result but a knee-jerk decree of ‘block all mail SPF fails for’ would be quite interesting in terms of support calls and perhaps short lived as a result.

Just order the remote sites to fix their configuration!

We do talk to remote sites about delivery issues. The problem comes when the remote site says ‘no’ either because they don’t understand the issue or because they don’t agree. There comes a point at which no matter what technical argument we make, the remote site will refuse to accept an issue exists. We have no authority to force them into any course of action.

As an example of this, most mail sending ‘rules’, as defined by documents called RFCs, have been in place for decades (the first one came out in 1982). There are still however lots of mail administrators that do not adhere to the basics and will aggressively argue against any such prodding. This includes small hosting companies, massive telecommunications providers and even some mail administrators in the university. Example problems include having a valid helo/ehlo (this one simple test rejects about 95% of inbound connections – spam – for a false positive of about one or two incidents a year). There’s also other issues like persuading the remote sender to send mail from a DNS domain that actually exists and having valid DNS records for the sending server.

Since we can’t get the internet to agree on what’s already established as rules for mail server for decades, it’s not likely that we’ll be able to enforce that a 3rd party site performs SPF checking.

Well what about DKIM?

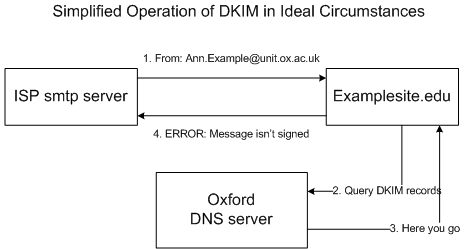

We like DKIM as a technology but in our environment we will hit similar issues as described for SPF. Before any technical contacts fill up the comments section, I’d like to make it clear that DKIM and SPF are not identical in what they do, but for the purposes of the problem being addressed in this article and for describing this aspect of their operation to end users they can be considered roughly similar. Here’s a very simplified diagram of DKIM in operation

In an ultra-simplified form, the difference is that DKIM adds a digital signature to each outbound message (more accurately, a line in the header, which cryptographically signs the messages delivery information) , which the receiving server is checking (using cryptographic information we publish in the DNS), rather than checking a list of valid source IPs. This would work great in a politically simpler environment and with all sites on the internet joining in. It wouldn’t end spam (an attacker could still compromise a users account and so send mail that was then legitimately received), but it would make spamming more constrained (such as to new short lived domains purchased with stolen credit cards and similar, which is a different issue) and by doing so you can use other anti-spam techniques more effectively.

- Again, the problems are that for a 3rd party site delivering to a 3rd party site, we cannot force the receiving site to have implemented DKIM

- If we state that all legitimate mail from ox.ac.uk is DKIM signed, then mail sent from gmail or nhs mail servers as ox.ac.uk addresses will be considered invalid by sites that do check the DKIM information for inbound mail.

In our team we’ve done some trials on scoring inbound mail based on DKIM and sadly there is a number of misconfigured sites out there that are sending what appears to be legitimate mail but that, according to the DKIM information for the domain, is invalid. As for SPF, we could increment the spam score slightly for invalid DKIM results to improve the efficiency of inbound mail scoring.

DKIM signing for outbound mail is a little trickier as we’d have to either share the private signing key with the 20 other units that are SMTP exempted and get them to implement DKIM. Getting the sites to implement DKIM I would say from my experience in talking to internal postmasters when reducing the number of exempted mail servers from 120 down to about 20 is near impossible.

Another solution would be to force all outbound mail connections for the remaining SMTP exempted mail servers to go via the oxmail mail relay cluster and sign at that one point. There are two problems with this. Firstly [please note that this is my personal subjective opinion] it isn’t a service with a dedicated administrative post, so any political emergencies in any other service leave the mail relay undeveloped/administered. This by itself isn’t a massive problem normally – the service is kept alive, the hardware renewed, the operating systems updated and there is some degree of damage limitation in a crisis. What is needed if the relay becomes the single point of failure for the entire organisation, is permanent active daily development – for example to proactivly stop the mail relay from ever being blacklisted. Otherwise a disaster occurs and the units that were forced to use the mail relay demand political allowance to connect to the internet directly (because they want to get on with their work, which is a legitimate need), and then DKIM has to be ripped out in order for those exemptions to work.

This leads onto the second problem in that forcing anyone to do anything needs a lot of political support, will be highly unpopular (some mail administrator have been independent for decades and have a setup similar to oxmail – a cluster, clamav and spamassassin), and people resent political upsets for a long period of time (as an example, a staff dispute that had occurred 25 years ago caused problems for an IT support call I worked on when I previously was employed in one of the sub units of the university).

Isn’t it simple? Just stop delivery attempts coming in to the university from outside that state the mail is ‘from’ an ox.ac.uk address?

This would currently block a lot of legitimate mail (users sending via gmail, nhs users etc). I anticipate that within a short time of being order to implement such a rule it would be ordered to be withdrawn due to the negative user impact on legitimate mail.

So, in summary, what are you telling me?

We can never totally stop a 3rd party site from accepting mail from another 3rd party site, where the sender is pretending to be an ox.ac.uk sender address. There will always be receiving sites that will not implement the technologies that can assist in that scenario and cannot be influenced or argued with.

If you want to send a mail to a 3rd party and have them know within (almost) perfect reasonable doubt that the mail is from you, then you require PGP or GnuPG to digitally sign each mail you send. Providing you become familiar with the process and don’t get confused into sending your private signing key to other people, an attacker would have to compromise your workstation in order to get your private signing key in order to sign mails as you, which is a large step up in complexity from simply sending spam.

We could make improvements to the inbound spam scoring to reduce spam coming in to the university in general, this takes time in order to find a point between the amount of spam being correctly identified and the amount of legitimate mail from misconfigured sites being left unaffected. A factor in this is that there are currently only two systems administrators for all of the networks services so human resources are an issue (this is not the only service with political demands for changes).

If there was a university wide policy that all mail from ox.ac.uk addresses was to be sent from inside the university, then we could implement SPF and (perhaps in time) DKIM, which could help reduce the problem of forged mail from/to external 3rd parties pretending to be form ox.ac.uk senders. In my opinion the university should fund a full time post dedicated to the mail relay if it wishes to do this however, since it’s not a simple task in terms of planning and political/administrative overhead.

And lastly, we know that spam is frustrating – spam costs the university in terms of human time but also dedicated hardware. There’s an actual financial cost to the university for spam. Why don’t we just stop it? There’s lots of anti-spam techniques we do actively use that I haven’t covered in this article and we do think about various improvements and test them but despite decades of the problem worldwide, there is no perfect anti spam system currently in existence worldwide. The university will therefore not have a perfect anti spam system until such time as one is devised. You may have less spam received using another organisations server, that doesn’t mean you were sent the same amount of spam.

I hope this article has been of some use. Please also check out the article from 2011 that was previously mentioned.