Empty Oxford CC BY-NC-SA Petros Spanou

On the 16

th March 2020, a message from the British Prime Minister was broadcast, asking everyone to stop non-essential contact with others (

https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-statement-on-coronavirus-16-march-2020). Students at the University of Oxford had already been advised to return home where possible (13

th March), and following the Prime Minister’s message, all staff were asked to work from home. As people gathered laptops, files, and office paraphernalia, few realised they would not be returning to classrooms, libraries, or offices for the next 12 months. Under tightening restrictions, students and staff adjusted to a ‘new normal’ way of life, working and studying remotely from offices set up in attics, kitchens, spare rooms, and garden sheds.

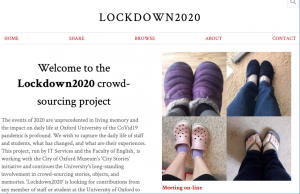

The University has seen pandemics and lockdowns before, and the college archives hold rich accounts of life behind closed doors. As the Covid-19 pandemic spread, and the country went into lockdown, various initiatives were set in motion to gather information and document this special time. One such initiative was Lockdown 2020, a small project run at the University of Oxford, using tools and methods previously employed to crowdsource memorabilia and stories from the First World War. Members of the University were invited to share their experiences and images through an online platform and the material was catalogued, preserved and made available online. The aim was not to gather a substantial, representative sample of material or to document the experiences of the whole University, but mainly to get a snapshot, a time capsule, featuring contributions from staff and students that could complement other official and unofficial accounts and sources.

One year on, the collection is still open and contributions are trickling in. The material gathered during the first lockdown (March-July 2020) has been analysed and some interesting observations have been made, for example about the language used in the submissions (see The Language of Lockdown https://medium.com/talking-languages/the-language-of-lockdown-cf0dae00fe7a). As the anniversary of the launch of the project is approaching, it may be a good time to reflect on the initiative also from a different angle, to look at the project and see what has worked well and what could have been done differently.

The idea for the Lockdown 2020 initiative came naturally to the team who has previously been involved in various community collections. A collection platform was already available, so it was a fairly simple step to set this up for the new collection. However, as anyone working on community collection projects will know, the technical infrastructure is but a small part of a project. A greater challenge is to reach potential contributors and encourage them to share their material. The Lockdown 2020 project started very small by reaching out to the most local of communities, the home department. As the submission form and process was refined, the collection was opened out to a wider audience. However, without anyone being able to dedicate time or effort to the project, communications and outreach was on a ‘best effort’ basis, often done through existing channels and, thus, reaching only a small section of the potential user base.

A marked changed came as the project was successful in securing a small grant from the Higher Education Innovation Fund and ESRC Impact Acceleration Account through the University of Oxford’s COVID-19: Economic, Social, Cultural, & Environmental Impacts — Urgent Response Fund. The funds were used to engage a project assistant to spend some time on the project. It was decided that the area to focus on was communication and outreach. The new team member spent time on promoting the project in general but was also able to successfully engage with groups and communities that the original team would struggle to reach, such as various student communities. Through these activities, the collection grew in size and, possibly more importantly, now features a wider range of contributors. It is still a very small collection, but interesting to note is that of the 200-odd contributions, about half were submitted during the six weeks when the project had a dedicated project team members who not only had the time but also the skills and channels to successfully promote the project and encourage participation.

The Lockdown 2020 collection will be archived and preserved. It can also be freely explored online. Although small, it covers a range of material and browsing through it is a good way to be reminded of what things were like a year ago, when working from home was novel, streets were empty and we were unused to seeing people wearing face masks. Looking at the project today, one year on, it is not only the content of the collection that can be interesting. For someone interested in community collections, or other forms of crowdsourcing, it may also be useful to consider some of the lessons learned from this simple project. The first one may be that this project has shown that you can generate something interesting and worthwhile even with minimal effort and resources. Following on from that, we can only emphasise the difference communication effort and skill cam make to a project’s success. Even a small injection of effort can make a big difference. One important thing to remember is that you never know what will happen to your project and how it will be affected by the context in which it is perceived and created. With that in mind, we may conclude that maybe our biggest mistakes so far has been in the naming of the project. But who thought we’d still be here, in lockdown, long after the end of the year 2020?

The collection is still open for new contributions from members of the University, and anyone can explore the current collection at http://lwf.it.ox.ac.uk/s/lockdown/. As you visit the site, you may notice that it is now called ‘Lockdown 2020 and beyond’. Lesson learned.

Finally, although community collections may be thought of as something involving objects or pictures, it can also take other forms. The Centre for Life writing are interested in literary and creative responses to this time, and are encouraging people to use life writing to reflect on this time, their situation or experiences. If the author agrees, contributions may be published on the website and featured in their Instagram account.

Finally, although community collections may be thought of as something involving objects or pictures, it can also take other forms. The Centre for Life writing are interested in literary and creative responses to this time, and are encouraging people to use life writing to reflect on this time, their situation or experiences. If the author agrees, contributions may be published on the website and featured in their Instagram account.

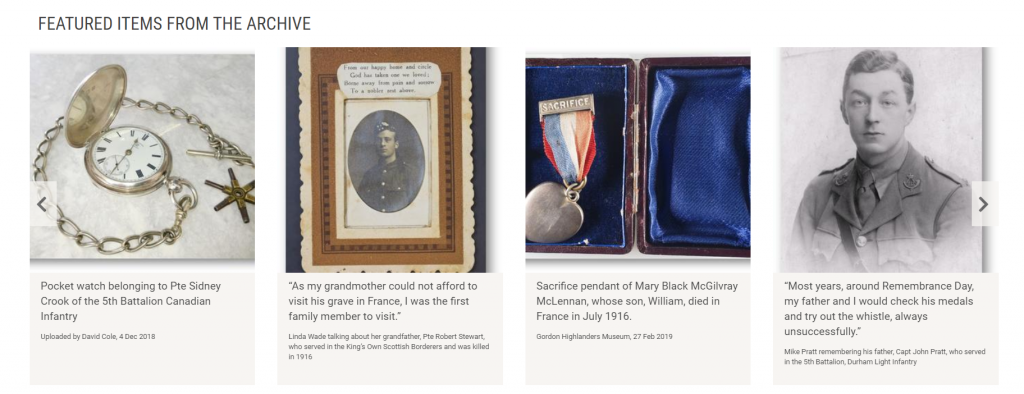

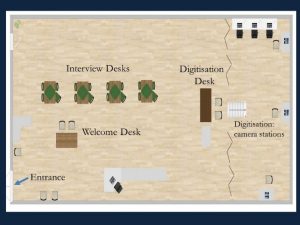

Lest We Forget is a University of Oxford initiative working with schools and community groups who want to run their own community collection events, digitising and sharing WW1 memorabilia and stories. It was launched in 2017 after a successful crowdfunding campaign. With additional funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project was then extended to run until June 2019, jointly led by the University of Oxford and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Lest We Forget is a University of Oxford initiative working with schools and community groups who want to run their own community collection events, digitising and sharing WW1 memorabilia and stories. It was launched in 2017 after a successful crowdfunding campaign. With additional funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project was then extended to run until June 2019, jointly led by the University of Oxford and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.